4 observations about the current state of AI in tech writing today

Photo generated by Midjourney when given the prompt: illustrated comic strip with four panels where a robot and human are doing fun things together like playing board games reading books drawing and giving each other hugs. Many images in this blog post will be variations on this theme from Midjourney.

Ever since Bing and ChatGPT launched in November 2022 and later had a huge media splash, I’ve gone through a full range of varied and sometimes conflicting thoughts and emotions about artificial intelligence.

Admittedly, I went through a brief period in early 2023 where I felt like artificial intelligence was over-hyped and actively avoided discussions about it. I also went through another brief period of Chicken Little fears that AI was coming for my job as a technical writer (which is not entirely unfounded, I must say). But aside from that, I’ve mostly kept an open mind and tried to stay curious about the technology. I’ve read nearly every article about AI that has crossed into my regular feeds and I’ve done some light experimentation with it.

With that in mind, I want to capture some of my current thoughts about artificial intelligence as they stand today. I will explore my thoughts on the impact of AI on society in general, but also on the tech industry and the field of technical writing in general. My goal isn’t to make predictions about the future, but to simply note some of my observations about the current state of affairs.

1. We should take the writing potential of AI very seriously

The first time I started to fully see the potential of what ChatGPT and related technologies could do was when attending a presentation by a fellow VMware technical writer Marco Anguioni entitled “How to Prepare for a Post ChatGPT World” that he had given at the 2023 Society for Technical Writers conference.

Marco explained how ChatGPT worked in depth, which was helpful as a solid introduction to the technology and its limitations and potential. (If you don’t yet understand the way LLMs work, I recommend researching this topic.)

Then, he discussed the findings of an internal AI study group that he had formed at VMware to explore the potential for using artificial intelligence in technical writing. This group met regularly to plan and design various experiments to test ChatGPT 4 and its potential use cases for various applications in technical writing. From these experiments, they determined that the most promising uses for ChatGPT for technical writing were:

- Automated content generation - Using generative AI to create initial drafts or specific sections of technical documents. This use case leverages the AI’s ability to understand context, follow guidelines, and produce content in a human-like manner.

- Content optimization - Involving generative AI to analyze and improve the quality of technical writing. The AI can review the content for readability, grammar, style, and adherence to guidelines, and suggest or make improvements accordingly.

- Summarization - Using generative AI to condense complex technical documents or concepts into concise summaries. This is particularly useful in technical writing where detailed, lengthy explanations can often be overwhelming for the reader.

- Technical FAQ generation - Generative AI can produce comprehensive Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for a product or technology based on common user questions and concerns. The AI can analyze a range of data sources, like user forums, customer feedback, support tickets, and product documentation to identify common queries and issues.

- Consistency checks - ChatGPT can ensure the uniform use of terms, phrases, and formatting throughout a document or across multiple documents. The AI can scan the content and highlight discrepancies in terminology or divergences from the prescribed style guide.

- Video script generation - Generative AI like ChatGPT can transform a technical documentation topic into a video script by first understanding the key points, processes, and concepts within the source material. It then structures this information into a logical and engaging narrative suitable for a video format.

However, Marco mentioned the main drawbacks of using ChatGPT:

- Entering proprietary and confidential information in GPT prompts poses significant risks, primarily concerning data privacy and security. By inputting sensitive data, you potentially expose it to unforeseen breaches, misuse, or unauthorized access.

- The OpenAI EULA (end-user license agreement) states that you cannot use content straight out of GPT for commercial use, which is a very important point for technical writing.

- The other risk is accuracy. By now, you’re probably familiar with the concept of AI hallucination. ChatGPT and other similar AI tools will always try to give you an answer, even if they don’t have the answer and they don’t have the data. So, it does occasionally make information up, with some fairly epic failures that have been in the news concerning the law and the airline industries.

Marco’s presentation was insightful, but one point in particular stood out to me:

Your job is not going to be replaced by the AI in the near future. Your job is going to be replaced by a human that knows how to use the AI.

It’s a sobering thought, isn’t it?

One other interesting point that captivated my attention was Marco’s point about would be the possibility of training your own AI fairly cheaply:

The cost for training GPT3 was in the tens of millions of dollars and it took a very long time. After GPT3 was released, there was a study and experiment made by Stanford called Project Alpaca that was conducted on Meta’s A.I. large language model Llama. Meta intended to gradually publicize the weights from their language model Llama through open source. Instead, they were leaked on 4chan. So, once they became public knowledge, people started making tests with them and running experiments.

And in this specific study, Project Alpaca, demonstrated that it is possible to train a language model. It is not as impressive as GPT3 or 4, but it is a small language model that I could run on my own personal computer. The cost can range between $500 to a few thousand dollars. Think about the difference between millions of dollars and a language model that is 70-80% as good as GPT that only costs a few thousand dollars and a few months to get there.

A quick sidebar related to the idea of cheaply training your own AI: I’m intrigued with Stephanie Dinkins' project where she trained an AI entity on oral histories supplied by three generations of women from her family. The AI can respond as a member of that family, which I find to have some fascinating potential. I am quite intrigued by the idea that I could train an AI to talk like me to my kids and future grandkids from beyond the grave. Let the haunting begin! 👻

If you still need yet another reason to take AI seriously, consider this quotation from a recent blog entry by Google technical writer Tom Johnson entitled AI is accelerating my technical writing output, and other observations (lightly edited for brevity):

During this project, I also did something somewhat superhuman. I needed to get lists of hundreds of different items for various hierarchical groups [listed in a spreadsheet]. I fed all of this into AI and it miraculously sorted it out and created a table of the items in an incredibly impressive way. … Needless to say, this task would have taken me a week to do manually, and it would have fried my brain in the process. By Thursday morning, I had a draft of the documentation [and] everyone thanked me for producing the documentation in such a short time. …

Overall, despite the challenges, AI empowers me to do things I previously couldn’t. Before, if someone had asked me for a user guide in two days, I would have pushed back and demanded at least a week. But now I’m like, sure, let’s see what we can do. It really depends on how much internal documentation you have at your disposal. Gather the right content, and you can work wonders with the right AI tools.

To reiterate my point: AI needs to be taken seriously by technical writers. For more information, I recommend following Tom Johnson’s blog I’d Rather Be Writing where he regularly writes about the potential for AI in technical writing.

2. That being said, we shouldn’t overestimate the quality of its creative output

Now, for all of the wonder of AI, I think we should resist the temptation to be fully mesmerized by its power. I was quite intrigued by the summary of a study conduct by researchers from GeoLab and Stanford that were reported in the recent March-April 2024 issue of Harvard Business Review. In their article entitled “Don’t let Gen AI limit your team’s creativity”, the authors reported on a study involving 4 companies (with 60 employees at each company) that worked in small teams on a real-life business problem their company was currently encountering. Each team had 90 minutes to work together to brainstorm solutions to the problem. Half the teams were instructed to use ChatGPT and half were not allowed to do so.

Then the ideas were evaluated and assigned grades (from A to D) by the people in the company who were tasked with owning the problem and choosing the go-forward solution. The judges did not know whether the ideas came from the groups using generative AI or working on their own. The findings were interesting:

The results upended the researchers' expectations. He and his colleagues had assumed that teams leveraging ChatGPT would generate vastly more and better ideas than the others. But those teams produced, on average, just 8% more ideas than teams in the control group did. They got 7% fewer D’s (“not worth pursuing”) but they also got 8% more B’s (“interesting but needs development”) and roughly the same share of C’s (“needs significant development”). Most surprising, they got 2% fewer A’s (“highly compelling”). Generative AI helped workers avoid awful ideas, but it also led to more average ideas.

Something that I found interesting was that:

Surveys conducted before and after the exercise showed that teams using AI gained far more confidence in their problem solving abilities than others did—a difference of 21%. But the grades they received suggest that much of that confidence was misplaced.

I’m reminded of a statement from Wharton AI researcher Ethan Mollick in a podcast interview with Ezra Klein in which he stated: “A.I. is good, but it’s not as good as you [an expert writer]. It is, say, at the 80th percentile of writers based on some results, maybe a little higher.”

My takeaway from this is that AI currently isn’t a replacement for an expert writer (such as a professional technical writer), but it can assist writers who are below the 80th percentile (which is most people). It’s probably a good tool for my dentist who once told me he paid English graduate students to write his college essays for him because he loathed writing so much. I could see ChatGPT helping him synthesize his thoughts and communicate competently, while still encouraging him to do the initial thinking and prompting.

Meanwhile for professional writers, AI may be able to help speed up or automate boring documentation tasks or be used as a collaborative tool for research and refinement.

That being said, it sounds like ChatGPT and other AIs are not yet able to achieve the excellence of an expert writer (at least, as of today). As such, we should avoid placing false confidence in the quality of ChatGPT’s output and should treat it more as a collaborator than a replacement. Expert human oversight is still needed. Continue to trust in your own judgment as a professional writer.

3. People might not yet be using AI as much as you may think

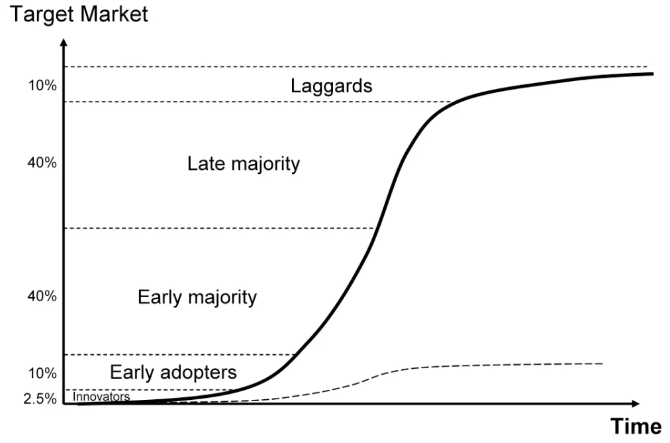

If you’re not already familiar with the Diffusions of Innovations theory by Everett Rogers, academics who have studied the adoption of new technologies have found that technology adoption looks like an s-curve:

The y-axis represents the passage of time and the x-axis of the graph represents the percentage of potential users (as opposed to all users):

- Typically, in the early stages of technological development, new technologies are used by a small percentage of users known as early adopters.

- The technology then moves into a stage of early majority where a new set of users tries the technology.

- In the late majority stage, the technology reaches a critical mass where it is used by most users generally.

- Finally, the last holdouts (the laggards) adopt the technology until every potential user is using it.

The speed of diffusion or the rate of adoption is determined by the characteristics of the innovation or its practical applications (such as its relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability). Whether a new technology increases adoption is often determined by the status of early adopters who are influencers within the group (yes, this is where that term originates from, in case you were wondering). Influencers generally occupy a high status within the group (because of their clout in the community) and they incite additional users to consider trying the new technology.

As Tom Scott notes, it’s kind of difficult to know where we are at on the s-curve of adoption with generative AI. A recent study from MeriTalk estimates that 31% of firms have adopted AI to date. If we assume that 100% of firms would be potential users of AI, that would suggest we’re in the early majority phase with this technology. (It is possible that not all firms are potential users of AI, in which case it would mean that AI technology is farther along in the s-curve of adoption.)

My anecdotal observations seem to confirm we’re in the early majority phase as well:

- The tech writers I casually discuss AI with all seem interested in exploring it more, but generally cite the fact that they’re too busy with their day-to-day work to delve deeply. This is the camp that I’m in too. I have experimented with AI through taking some guided courses. But even though I’ve been interested and would like to experiment more, it’s hard to find the time to work it into my daily routine. I suspect I’m not the only one who can’t keep pace.

- Tom Johnson observes: “Very few technical writers seem to even be using AI in their writing workflows. Many are still searching for those use cases where AI will unlock some gain.”

- The NY Times journalist Ezra Klein recently said: “I find living in this moment really weird, because as much as I know this wildly powerful technology is emerging beneath my fingertips, as much as I believe it’s going to change the world I live in profoundly, I find it really hard to just fit it into my own day to day work. I consistently sort of wander up to the AI, ask it a question, find myself somewhat impressed or unimpressed at the answer. But it doesn’t stick for me. It is not a sticky habit. It’s true for a lot of people I know.”

- The early adopter Atlantic journalist Ian Bogost uses AI consistently, but talks about how the initial magic of using AI is now gone for him. He writes about the wonder and awe he felt when first using ChatGPT has disappeared as “slowly, invisibly, the work of really using AI took over. … The more imaginative uses of AI were always bound to buckle under this actual utility. … If the curtain on that show has now been drawn, it’s not because AI turned out to be a flop. Just the opposite: The tools that it enables have only slipped into the background, from where they will exert their greatest influence.”

- A few months ago, I had a conversation with a UX researcher who talked about the research they did at a conference with technical professionals to learn where they were at in their current use of AI in their company. It could have been a fluke of the people he talked to, but these professionals seemed largely naive or woefully unaware of the potential uses of AI at their firm. My guess is they were not using it very widely or exploring its potential much.

To me, this anecdotal evidence suggests that we are at an early majority stage in the s-curve of AI adoption, characterized by people having heard of the technology and being interested in exploring more. However, we are not yet at the tipping point of social change brought on by widespread adoption. A sizeable number of people still have yet to fully adopt and begin using the technology extensively. They’re possibly waiting for more social proof, clearer use cases, or better knowledge about how to use the tool before jumping in themselves.

It’s for this reason I’m not yet worried about AI replacing my job as a technical writer. I agree with Annie Lowery’s observation in an Atlantic article entitled “How ChatGPT Will Destabilize White-Collar Work”:

In the most extreme iteration, analysts imagine AI altering the employment landscape permanently. One Oxford study estimates that 47 percent of U.S. jobs might be at risk. … [However], people and businesses are just figuring out how to use emerging AI technologies, let alone how to use them to create new products, streamline their business operations, and make employees more efficient. If history is any guide, this process could take longer than you might think.

If we are indeed in the early majority stage, that means we don’t know how long it will take before adoption reaches critical mass. For some technologies, it takes several decades before new technologies have a noticeable impact on our daily lives (about 30-40 years for the Internet, for example), whereas some are quicker (such as smartphones, which took about a decade). I don’t know which one AI will be or when it will reach critical mass, but I don’t suspect it is coming right away. It’s still too new for that.

So, where does this leave us? What should we do with AI as technical writers?

4. For now, I recommend experimenting and keeping an open mind

If we are indeed at the early majority stage, I think there are two logical ways to approach AI as a technical writer:

- You could wait for wider adoption to let other people build out streamlined workflows for using AI. When you have more social proof, you could consider using it yourself. This approach has the advantage of not wasting time experimenting and potentially failing to find meaningful use cases.

OR

- You could jump into the early majority and begin experimenting yourself so that you can be ahead of the s-curve before greater adoption comes. The advantage of this approach is that you might be able to learn how to use the technology before other technical writers, giving you a competitive advantage in the job market. Or if/when your employer adopts it, you could at least be ready to quickly and flexibly slide into using it at your company.

For me, I plan to take the second approach. I am a curious person who loves to learn and experiment naturally and I have enough years left in my career where I think I should take the technology seriously. I am forming a plan to take Ethan Mollick’s advice to try using AI regularly, especially for things that I am generally good at doing so that I can really evaluate where AI shines for me and where it falls short.

To that end, remember I mentioned that internal AI study group at VMware? Well, unfortunately that group was disbanded shortly after the Broadcom acquisition. But I’m bringing it back now with a few other technical writers in my business unit, which is pretty exciting. We’re going to start meeting every other week. In the weeks where we meet, we will brainstorm experiments and use cases for generative AI in technical writing. I think it will be good to see if AI can solve some of the immediate challenges or problems we are currently encountering. In the off weeks, we’ll each independently run these experiments and then share the results of the experiments at the following week’s meeting.

I’m excited for this group because I like being accountable to a group for this kind of technology experimentation. It helps me stay on task, to see different perspectives or approaches, and it holds my feet to the fire to ensure I actually follow through on my intentions. If this sounds good to you, you could consider setting up a similar study group at your workplace or even with a few like-minded technical writers in your area.

If you want to go on your own learning journey, here’s a few resources to get you started:

- LinkedIn Learning: How to research and write using generative AI tools

- Cherryleaf: Using generative AI in technical writing

- I’d rather be writing: Prompt engineering for tech comm

Happy exploring!

Sidebar: Dall-e was just not as impressive as Midjourney at generating high quality images. This was maybe the best image it generated using the same prompt that I used for Midjourney. Some of the images were really, really disturbing. But this one was okay (I guess):